Lesson 1 of 0

In Progress

Lesson Four: Understanding Generational Trauma

In this lesson, we more deeply examine how trauma is passed from one generation to the next. The experiences we have as children stay with us as adults. We heal, and we change our behaviors, only when we become aware of how our traumas have affected us.

The ACE study started in 1995. Vincent Felitti MD and Kaiser Permanente’s Department of Preventative Medicine recruited some 17,000 people in an ongoing study. The ACE study looks at how negative childhood experiences affect the participants as they go through life. It has been ongoing since the mid-1990s.

The study was developed after discovery that 50% of clients at Kaiser’s obesity clinic dropped out of the program, despite successfully losing weight. A majority of these people were found to have experienced childhood sexual abuse. The initial findings suggested that weight gain served as a coping strategy for emotional pain (depression, anxiety, fear.)

The ACE study looks at ten common adverse experiences in the household:

- Being regularly put down, humiliated, or yelled at by a parent or adult

- Being pushed, grabbed, slapped, or thrown, or hit hard

- Being touched, fondled, or having sexual activity with someone at least 5 years older

- Feeling like we weren’t loved or important or special by family members

- Not having enough to eat, or clean clothes

- Parents frequently drunk or high and unable to adequately protect us

- Parents separated or divorced

- Domestic violence in the home (mother or stepmother hit, grabbed, pushed)

- Living with someone in the home who was a problem drinker or used street drugs

- Having a mentally ill, depressed, or suicidal family member

- Having a family member go to prison

Each of the above experiences, if present in a child’s life, is one point. The higher the point score, the higher the risk of addiction and other problems.

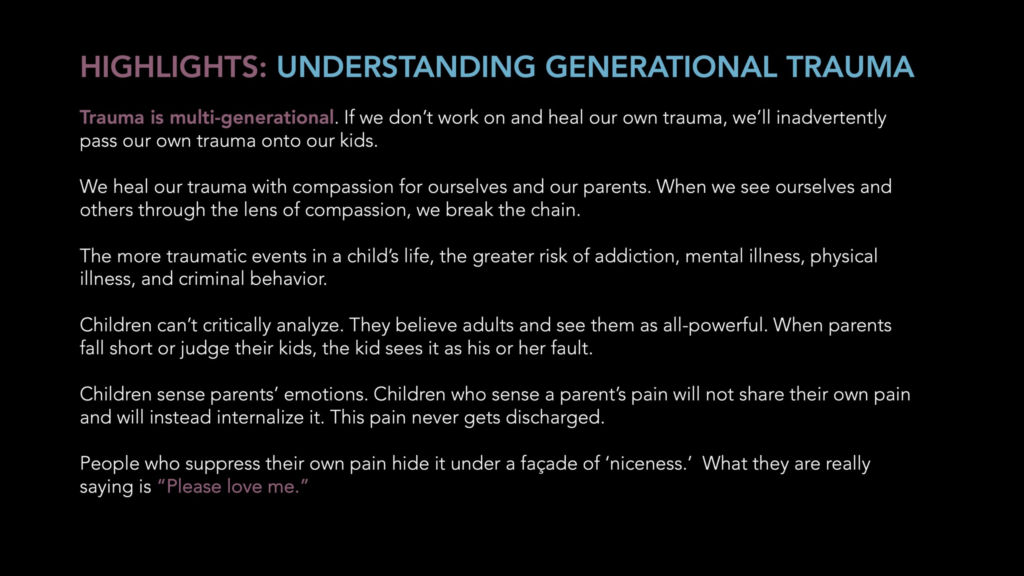

From this research, we know that almost any kind of childhood trauma increases our risk for addiction, juvenile delinquency, obesity, mental and physical health conditions. The risk increases exponentially for those of us who have experienced multiple traumas. For example, a male child with a score of 6 or higher is 4600% more likely to become an IV drug user than someone with a score of 0.

As previously discussed, our early childhood experiences are crucial to how we experience the world, because the experiences we have form how we view the world. If we see it as safe and secure, we’ll likely view the world as a good place. If we view it as unsafe, we’ll perceive the need to protect ourselves.

The ACEs all represent, in one way or another, a fracturing of the basic relationship with our caregiving parent. We might learn that our environment is not safe, that we aren’t loved, that our needs won’t get met, that the people who should protect us might hurt us. But we must also be able to survive, and without attachment to our caretaking parent, we would die. So we adapt our behavior to maintain that connection, no matter how unsafe, unsupportive, unloving, or harmful.

We put our own needs aside in order to survive. We learn not to ask for what we need. Or maybe we become children who are caretakers of our parents. Or we “protect” them by not telling them when we’re being hurt, because we sense they can’t handle it. Or we cover up our negative feelings, because we’ve been told not to cry or get angry.

What happens when we push all of these unmet needs down? What happens when we can’t share our anger or grief or fear from something that happens to us, because we don’t feel it’s safe? What happens when we lose out on our own childhood because we’re busy trying to be an “adult” to care for our parents or siblings? Here are some examples:

- We push down our needs. We “depress” them. And we become depressed.

- We hide our anger, so it boils up deep inside us

- We cover our loneliness and grief with caretaking or pleasing behaviors

- We develop a thin veneer of happiness, as though everything is perfect and good

These are behaviors we learn early in life, but they are imprinted on our brain. And they actually influence how our brains develop. Without the constant loving attention of our caregiving parent, the neural pathways associated with calming, safety, security don’t develop. The pathways that motivate “fight or flight” overdevelop. And our perception of the world is formed based on what we learned.

Those thoughts, beliefs and behaviors stay with us as we become adults. They influence how we perceive others. How much we trust. How secure we feel. How well we can love someone. How much we love ourselves. And, perhaps most crucially, what we give to our children.

Even as much as we promise ourselves we will be better parents than our parents were, unless and until we have really worked through our trauma, we will inadvertently pass on to our kids attributes of what was passed on to us. Even when we try our best. It isn’t genetic; it’s just how our brains becamewired by what we experienced early in childhood, from our own parents. And they learned it from their own parents. And so forth. So when we look at it that way, we can’t blame our parents (or ourselves.) We all did the best we could at the time, but now we can begin to examine it. By examining it, we can interrupt the cycle of generational trauma.

The good news is, once we begin to understand why we’re behaving the way we are, and what’s driving it, we can begin to rewrite the story in our unconscious, and begin to change our behaviors. As far as our kids, the good news is, kids are resilient. So even though none of us are perfect parents, and we’ve all made mistakes, we can change now. And as we change, we repair the bonds with our kids. That rewires their neural pathways and helps them to be healthier and happier.

As adults, we have the capacity to look at what we went through, and make sense of it. We can realize that our parents were genuinely trying, and wanted to be able to love us, even if they weren’t able to do so. But our capacity to see that comes from our mature brains. A child’s brain has almost none of that capacity.

Children see the world in a very self-centered way. Up until their early teen years, most children assume that the world revolves around them. It’s just how their brains are wired. So, for example, if Dad works all the time and is never around for us, we assume that we’ve done something to deserve being ignored. Or maybe we think we just aren’t important.

If Mom drinks all the time, and isn’t around for us, our childhood perspective doesn’t see her as having a disorder; we assume that she loves the alcohol more than she loves us. And again, we believe we’ve done something to make ourselves unlovable. If our caregiving parent is depressed or anxious or angry, again… we assume it’s something we did that made them behave that way. We learn to believe that we’re a bad person.

Even if our caregivers tell us otherwise, children have a remarkable ability to sense emotion. They know when parents are angry or happy or sad. So that can actually be even more confusing: we clearly can tell that Mom is depressed, but maybe she tells us everything is fine. We know it isn’t, but we can’t make sense of what we’re being told. So we learn not to trust when we’re told things.

Now… what happens if we are constantly devalued, humiliated, embarrassed or made fun of? Well, basically the same thing: If it comes from our parents or caregivers, we assume it’s true. If it happens to us in school, a lot depends on what happens when we go home. If we tell our parents, and they tell us to handle it ourselves, we learn that we aren’t safe and don’t have help. Or maybe we don’t tell them at all, because we’ve already learned they can’t handle our pain, or won’t listen, or are too busy. We learn that our needs won’t be met, so we shouldn’t ask.

All of these influence how we form our perspective of the world, what we believe about ourselves, and how we interact with the world. And unless something happens, such as serious self-reflection, outside help, or discovering healthy relationships, those beliefs stay with us throughout our lives. These beliefs are often below our conscious thought, and influence how we think, how we perceive, and how we behave.

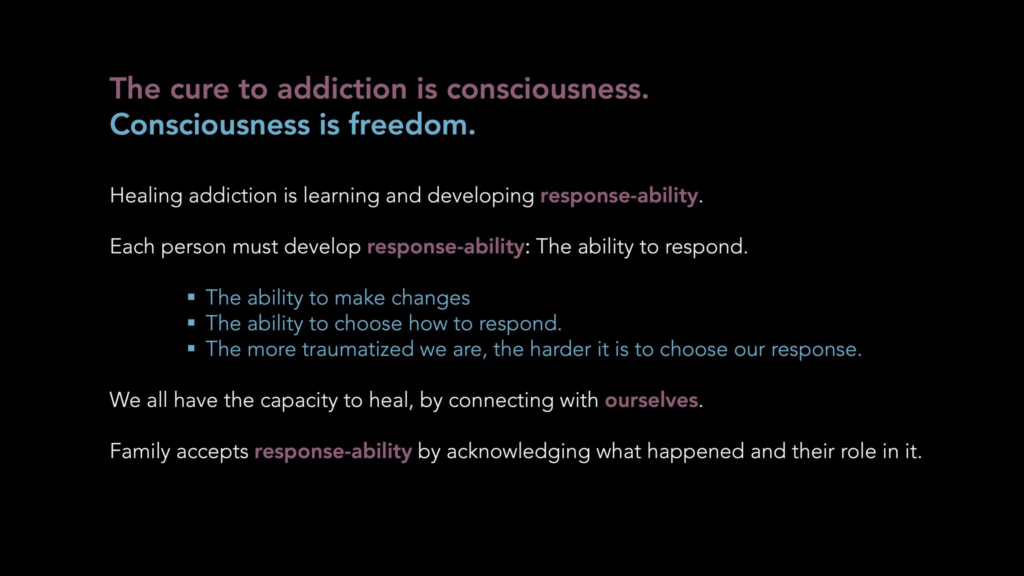

Again, as we understand these thinking errors, distorted thoughts, and ineffective behaviors, we can begin to change them. Knowing why we do something helps us let go of that old, ineffective behavior. We know that they helped us at one point, but don’t serve us now. We can be thankful that the behaviors kept us safe, and we can let them go and form new, more effective behaviors.

The perceptions and beliefs we learned early in life continue to influence us on a daily basis. But we often don’t realize this is happening, because it’s buried deep in our unconscious. We are often not even aware of it in the moment it’s happening. And until we’ve really worked on our trauma, we won’t even realize it after the fact.

One example: If we see our mother drinking constantly during our childhood, we will perceive that Mom loves her alcohol more than she loves us. It may not be factually accurate, but it’s what we will perceive. Decades later, we realize that Mom has a disorder, and it has nothing to do with anything we did, and that Mom loves us as much as she is able. But let’s say Mom does something that really upsets or disrespects us. Many of us, in that example, might find ourselves getting explosively angry, way beyond what’s warranted by what Mom did.

What’s happening with our rage in that moment has nothing to do with what Mom did in that moment. Instead, our brain is triggered to an experience we had decades ago, as a small child. We felt unloved, like Mom was choosing her bottle over us. We couldn’t get angry then, because we’d lose attachment. So we pushed that anger down. Now that we’re an adult, that anger can slip out, because we know we no longer need the protection. And the anger is the unresolved anger of the 2 or 3 or 5-year-old child. So we find ourselves regressing and behaving with a 3-year-old’s brain, because that’s what got triggered.

Here’s the part that’s really annoying: Even once we understand that this is happening, we can’t just simply change the behavior. It’s coming from our unconscious, and can pop out before we’re even aware of it. So we have to practice improving our self-awareness, and learn to look for situations that might trigger those behaviors, and learn to respond differently.

There are lots of other examples that might be happening, depending on our specific experiences. This is only a tiny number of examples:

- In relationships, we push others away because we’re afraid we don’t deserve them, and they’ll leave, so we take control by leaving first.

- We distrust everyone

- We sabotage our own success because we don’t believe we can be successful.

- We lash out at people because they triggered an old (unconscious) memory or feeling

- We shy away from sex because it unconsciously reminds us of being hurt

- Or the opposite: we’re promiscuous, because it’s the only way we knew to get attention

- We eat very quickly, and more than we need, because food wasn’t plentiful growing up

Attunement, in therapeutic terms, means connecting in a deep, meaningful way. If, as a child, we’re attuned to our parent, child and parent are gazing into one another’s eyes, and feel a sense of genuine connection. For adults, attunement means we “get” each other. We care and respect one another deeply. We hear them and they hear us. We understand each other. We can perceive what and how another is feeling.

Attunement feels good because we’re being seen and validated. But because we’re hard wired for connection, it also feels good because we’re connecting vulnerably and authentically with someone else. And when we are attuned, our brains are firing the brain chemicals endorphin and dopamine, which create both a sense of safety and calm, and a sense of interest and motivation.

The even better news is, as these brain chemicals fire, they enhance and strengthen and rebuild our neural pathways. Basically, they make the “highway” bigger. If we are in an attuned connection with someone, we will, over time, be able to feel more calm, safety, joy, interest, and motivation.

To break the chain of generational trauma, we can cultivate friendships and relationships where we feel attunement. There are important attributes of attuned connection:

- Nonjudgmental listening

- Compassion (connecting with the experience of another and seeking to help)

- Empathy (the ability to experience in ourselves what another feels)

- Agenda-less listening (truly hearing the other person without forming a response)

- Reflecting back what we’ve heard, to make sure we “got it right”

- Recognizing that others’ behaviors are rooted in trauma, seeing them with compassion

When we’re able to be present with someone, holding the above attributes in our interaction, we feel attuned. We grow, and our brains cultivate new “highways” for the brain chemicals that make us feel good. Over time, as these highways develop, it decreases cravings, reduces the discomfort of mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and anger.

Practical Strategies for Better Attunement, Connection and Communication

In order to form the best, most effective communication patterns with others, we can:

- Put blame and shame aside.

- Own what you did. This will require working on your shame.

- Both family members and addicted person must own responsibility.

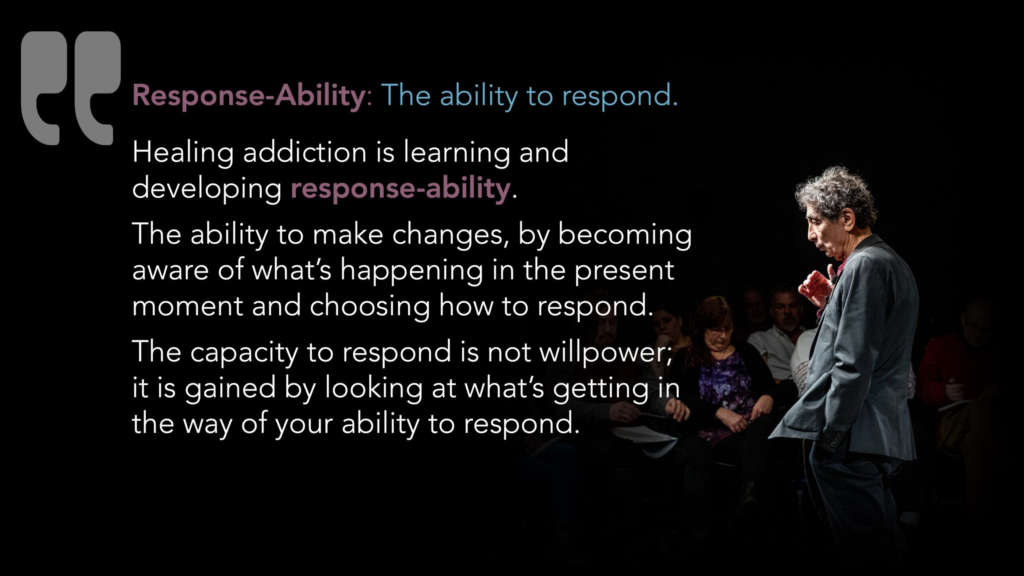

- Response-Ability: The ability to respond. This is crucial for healing addiction.

- Self-awareness: This is crucial for response-ability. Otherwise, our unconscious will prevent us from taking responsibility.

- Knowing the truth will liberate you. It isn’t the truth itself, but knowing it, that does so.

- If we’re triggered, think “Am I still 4 years old? Does it matter what others think?”

- In an uncomfortable experience, ask yourself “Is this the first time you’ve perceived this? If not, think back to the first time, and be curious about how it’s affecting you.

- Learn to rely on ourselves, instead of others, to feel worthy. Externalizing worthiness means we’ll never feel worthy.