Lesson Five: Beyond Codependency & Victimhood

Lesson five explores the concept of perception of self and others, and how our perceptions (and the things that formed them) influence how we experience the world.

Most of us get confused now and then with the difference between feelings and perceptions. That can get us into trouble. The difference isn’t difficult, but does requires us to be thoughtful.

Feelings are pretty simple: we feel mad, glad, sad, or afraid, and that’s about it. These are the four basic emotions. Pretty much any other emotion we can describe is made up of one or more of the basic four.

But what if I’m feeling disrespected, upset, confused, unloved? Well, those aren’t feelings. They are perceptions. They are my interpretations of circumstances I’m in. Now think about it again. What underlies “disrespected”? Well… If we feel that, we probably feel hurt, and not listened to. So for most of us, the underlying feeling of disrespect would probably be sadness and perhaps anger.

Now, while “unloved” is not a feeling, the perception of the experience is what we are describing. The meaning or value we have attached to an experience we’ve had. Here’s the difference: Feelings are real. If we are sad, we are sad. If we are happy, we are happy. But perceptions are different. They are made up of observations and interpretations, and are filtered by prior experiences.

In [Lesson 3: Exploring Our Trauma], Gabor works with two individuals who were mad at something that happened. Upon further exploration, these people realize they made assumptions about the intent of the person they were mad at. So the “feeling” was not disrespect or devaluation. That was a perception, that arose from an interpretation of behavior. Audience members pointed out that, in fact, there were many different ways to interpret the behavior. Upon considering this, the individuals both recognized that they had “made up a story” about what the intent was behind the behavior.

So the question then is… where did that story (and the assumptions and perceptions that went along) come from that created the anger?

How do we make these interpretations? Well, they are heavily influenced by the experiences we have, especially those from early in life.

One of the most powerful tools we can use to understand this is to think back to the first time we remember feeling this feeling (or experiencing this perception.) In nearly all cases, it goes back to a time early in life.

As we’ve previously discussed, as infants and small children, we’re hard wired to maintain attachment with our caregiving parent no matter what. Without the attachment, we’d die, as we’d be unable to care for ourselves. So as children, we learn to adapt our behavior.

Here’s one example: If, when we were small, we were belittled or bullied or made fun of, it undoubtedly hurt us. And to survive, we learn to adapt. To tolerate the bullying. To ignore it. To laugh it off. To please the bullying person. Each of us might respond slightly differently. And that behavior we learn is effective; we survive, we maintain connection. If the bullying (in this example) continues, we get really good at the adaptive behavior, so much so that we might not even be aware we are doing it.

But when we grow up, those behaviors are deeply embedded in us. Even when we consciously know that the current situation is different. We may not even think about what happened to us… but a part of us knows. And so, in the example above, our first thought, driven by what we learned to survive, is to assume the worst.Because that’s what we learned to protect against.

So when our unconscious self is reminded of an early experience, that part of our memory is triggered. Suddenly, our two-year-old or five-year-old self is responding, protecting us. Because it does not realize we don’t need that protection any more.

So hopefully it is more clear how our past experiences influence our current experiences and perceptions. We don’t objectively view much of anything. Everything we take in is experienced through these “filters.” The filters exist below our conscious awareness, and color and change how we experience things in our world. This is true of nearly everything in our lives, from day-to-day interactions, to expectations, to relationships. The things we believe, whether or not we feel safe, how much joy we experience. Literally everything.

Gabor speaks about it in the words of the Buddha, “With our thoughts, we make the world”, and then adds “But before that, the world creates our thoughts.” That really sums it up: Our perception of the world greatly affects what the world is like for us. And our perceptions are formed by the experiences we had growing up. It remains that way until we actively become aware of this, and seek to change those perceptions.

When we begin to change our perspective, though, it isn’t just an intellectual exercise. We must also process the emotions that go along with that. There are many ways for doing that. Insight-based psychotherapy is very effective but time consuming. EMDR or Brainspotting can also be highly effective. Psychotherapy using Internal Family Systems, which Gabor uses in part, is another gentle and effective way to approach this.

Even seemingly minor traumas that we experience in childhood make it impossible to be in the present moment. When someone says “that’s triggering for me”, that is a past trauma that is

taking them out of the present moment. When that happens to us, we are transported back to the triggering moment.

In this segment Gabor refers to a “trigger” as a mechanism to deliver lethal, explosive ammunition. When we are triggered, we are the ones containing the explosive material. Someone says something that triggers us, and we explode, or act out, or release what we are carrying. So Gabor suggests that, in a way, we can be thankful for the triggering person or event. (Bear with me here.)

What happens if we approach being triggered with gratitude and curiosity? At first that sounds preposterous, yet it gives us an opportunity. Instead of staying angry and upset, we can appreciate that we have discovered something about ourselves that we need to look at. And the person triggering us is simply a messenger, someone who, perhaps inadvertently, is bringing our attention to this issue we can explore. So the trigger is something we haven’t noticed before. Or perhaps we’ve noticed, but been afraid to explore it. The trigger is a form of protection, it says “stay away from this.”

And yet, when we approach it with non-judgment, curiosity, and self-compassion, it doesn’t have to be scary. We can examine where that feeling came from. What happened, objectively. We can separate feelings from perceptions. And we can choose to respond differently in the present. We can recognize that the present is different from the past. And we can free ourselves of those triggers, because they no longer serve us, even if they did at one time.

When we’ve been traumatized, we’ve experienced victimization. We’ve experienced something harmful, hurtful, painful. In the video, Gabor talks about Lindsey, the individual who experienced her mother’s drinking. Lindsey experiences herself as a victim of her mother’s drinking. Lindsey was indeed victimized by her mother’s drinking, in that it occurred, and it affected Lindsey.

The crucial point is, that victimization does not automatically lead to victimhood. Victimhood happens when someone is victimized, but victimhood happens when we give up our power over the situation. We cannot change the fact that we were victimized, but we can choose what we do now that it has happened. As soon as we reclaim and own our power, we’re no longer a victim. And this applies whether we are the addicted person in a family, or a family member. When we take our power, then we choose how we respond. We become, as Gabor puts it, “response-able.”

Judgment is one of the biggest barriers to connection. It flows in two directions: judgment of self, and judgment of others.

For those who are struggling with an addicted loved one, it can be difficult to let go of judgment. We want something to pin the blame on. Often the blame is directed at the addicted person:

“If only you listened to us…”

“If only you didn’t hang out with those people…”

“If you tried harder…”

Other times, blame is directed at ourselves…

“I should have noticed earlier…”

“I should have spent more time with her as a child…”

“I shouldn’t have been so angry…”

And for the addicted person, there’s just as much blame to go around:

“You really were terrible parents. This is your fault…”

“You are always yelling at me, and that makes me want to go out and use…”

“If you just quit bothering me, I could get well by myself…”

The truth is, blame isn’t helpful. What we’re doing with blame is trying to discharge our discomfort, which arises from our own shame. (Shame, remember, is the overwhelming belief that we, as opposed to our actions or feelings, are bad; and are not worthy of love and belonging.)

For the addicted person, we can recognize that, as Gabor stated, all addictions are an attempt to solve a problem and escape from suffering. That problem is that of emotional pain, loneliness, suffering, and from shame. Our shame comes not from the fact that we are addicted; we are addicted because we are ashamed.

Likewise, for the family and friends of an addicted person, we can look at our own behaviors, beliefs, and worthiness. Though our coping strategies might be different than those with addictions to drugs or alcohol or gambling or sex… etc.., all of us have something that we use to cope. For some it might be control or codependency or perfectionism or workaholism. If we think about our own coping strategies, most of us can see our own imperfections. Often those imperfections play out in how we interact with our addicted loved ones.

Addiction is rooted in trauma of some form, which creates an emotional wound. That wound narrows our capacity to experience the world. It impacts our perceptions. It shows us that the world is not a place to be trusted. For a child, whose view of the world is very self-absorbed, even a small event can create trauma. This, in turn, impacts the child’s sense of the world, and with limited capacity, the child will handle the trauma the only way s/he knows how. Usually this is by internalizing the emotions s/he could not express.

But eventually, those internalized emotions don’t stay internal. If we push them down too much, depressingthem, we might end up with depression. Or we might have anxiety that eventually becomes overwhelming. And then, we start to medicate with whatever we can find. It might be a drug or alcohol. It might be some form of acting out, sexually, or with shopping or gambling. It might be losing ourselves in a world of video games. Or immersing ourselves in work. All of these are different forms of addiction, and all of these are an attempt to deal with the pain of the wounds we suffered.

So we can look at addiction as an attempt to solve a problem, as a way of dealing with, or numbing, emotional pain. Doing so makes it easier to let go of anger and judgment, and replace it with compassion.

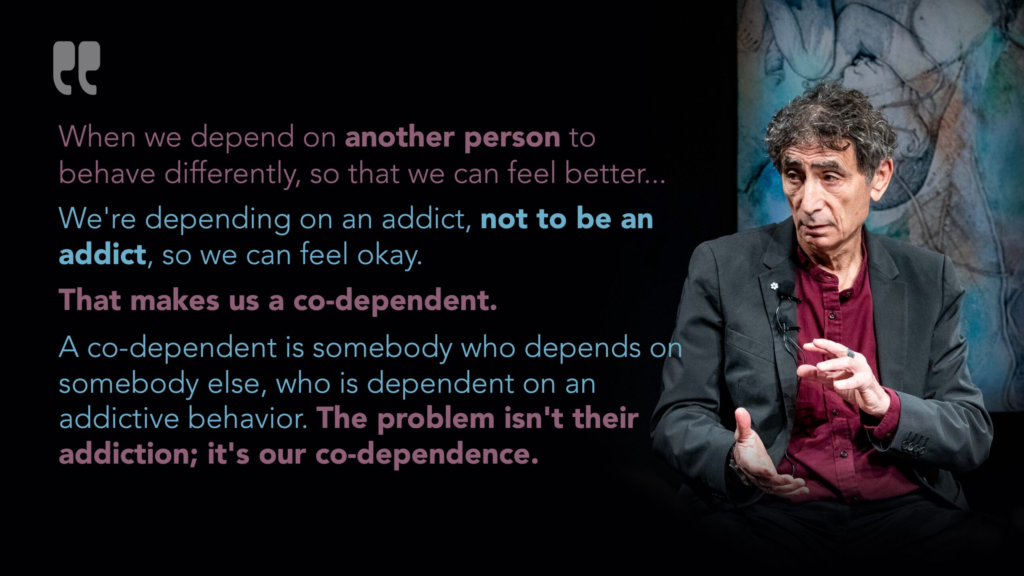

Codependency is, like triggers, perceptions, and just about every other part of ourselves, a function of what we learned as children. It has many facets, but a key part of it is a strategy of connecting our value or worth to what someone else does or doesn’t do. And co-dependency, as its name implies, requires two or more people. Typically, one is caretaker or ‘enabler’, the other is the dependent. Often, the roles between the two interchange. But it isn’t a one-way relationship; the enabler often gains a sense of worthiness, a means of control, or some other benefit, while the dependent is, in some way taken care of. It is rarely an effective relationship in the long term.

Codependency is a topic that has entire books written about it. Our discussion in this lesson is in the context of addiction and families, where codependency is nearly always present. But before we go further, note that codependent behaviors are learned from our parents and the environment we grow up in. Our parents, in turn, learned it from their parents. No one wakes up and decides to be codependent, and no one intends to behave that way. So let’s put aside any judgment or shame,

Regardless of whether we’re the dependent or the enabler, codependency interferes with autonomy. It makes it hard to think for yourself. It makes for blurred boundaries. And many people use the word in a way that’s dripping with judgment or accusation: “Stop being codependent.” “If you weren’t so codependent, I could just live my life.” But if we can view codependency through the lens that Gabor is showing us, we might see a different perspective.

Think about codependency, boundaries, and what we’ve already learned about perception. Codependency, whether we are enabler or dependent, is driven by perceptions that are filtered by our earlier-in-life experiences. It’s further complicated by the intertwined nature of the connection between the codependents. All of these pieces fit together.

In our addiction-affected families, we often hear from the enabling person “I have to save him” or “She needs my help” or “I can’t just let him be on the street” or something similar. Conversely, we hear from the dependent person “I wish she weren’t so controlling” or “I wish she’d leave me alone.” Of course, we hear the opposite messages as well: “Why won’t you do this for me”, or “I can’t take this anymore.” Codependency represents a constant struggle between competing desires and needs, which are rarely met. Everything comes with strings attached. Both parties struggle with resentments toward each other. Boundaries (on both sides) are rarely respected.

In short, nobody’s happy. And that’s because our unmet needs and our filtered perceptions are getting in the way. If we’re an enabler, we probably want to be loved and appreciated. Or to feel needed. Or to gain control, so we don’t feel out of control. If we’re a dependent, we probably aren’t good at asking for our needs. Or we don’t feel confident. Or we don’t feel lovable. (Yes, a lot of those “feels” are perceptions, not needs. They’re used here for language simplicity.)

So much of the web of codependency is driven by perception and unmet needs. Here’s the catch: Understanding it intellectually doesn’t mean we can just change our behavior. We’ve spent decades learning it. The underlying behaviors and perceptions allowed us to survive. So it will take time to learn new, more effective strategies.

One of the first things we can do is simply acknowledge our behaviors. Talk to the people we’re connected with. Have conversations about codependency. Own our own behaviors, and ask the other person to acknowledge theirs. Agree to gently, respectfully, and lovingly point out or remind each other when we’re acting with codependence.

And… we can give ourselves, and those around us, permission to be imperfect. To fail. To fall into old patterns. We can recognize that overcoming these behaviors is a practice. It’s not something we achieve and are done with. When we do that, it’s much easier to accomplish.

For those of us who are on the enabling end of the spectrum, it can be scary to let go. To step back, and to give up control, judgment, and expectation. But when we do this, often, something wonderful happens. The person we’ve been tangled up with suddenly feels the freedom of not being controlled. S/he doesn’t have to worry about disappointing you. There’s no fear about what happens if s/he fails. With the loss of that pressure, and those expectations, very often the person can now feel free to actually improve him or herself. Maybe they’ll ask for help from someone other than you. Maybe they’ll ask you, but in a different way.

And for those of us who are dependent, having boundaries, and letting go of the codependent support we may have relied on can also be freeing. We may suddenly feel our sense of worth improving. We might discover that we can now make our own decisions. Even if they aren’t perfect ones, we learn, and we can get better.

Nothing about this process is easy. But we can approach it with love, compassion, and non-judgment. Curiosity. An open mind. A recognition that no one is at fault, no one is to blame, no one is trying to harm the other person. With that perspective, we communicate better. We have clearer, more effective boundaries. We can find our worthiness within ourselves. And ultimately, that helps us live happier, healthier lives.