Lesson 1 of 0

In Progress

Lesson Eight: The Cure to Addiction

In lesson eight, we bring together the most important elements to attain long-term recovery from addiction. From Gabor’s perspective, this involves cultivating a support system for the addict that helps to rebuild brain pathways. It also includes discussion of readiness for recovery. The lesson closes with a short review of some of the most promising psychotherapeutic approaches and additional tools that help achieve and maintain recovery.

As we discussed in the previous lesson, it isn’t easy to draw a clear line between codependent enabling and supporting someone in a healthy and effective way. Part of the reason is that the line isn’t always clear. Another part of the reason is that the exact same behavior or action can be enabling in one circumstance, and helpful and effective in another. How can that be?

Enabling is driven by the expectation of outcome. The answer lies in in our intent and goal when we’re providing the help or support or enabling. You will remember from the last lesson that when we enable, the action of enabling provides some sort of benefit to us. Maybe we get a sense of control. It might be connected with our sense of self: “It’s my job to rescue my loved one! I can’t let him down!” It might be a desire to provide to our loved one something we never got.

In short, enabling provides us with some level of relief or comfort or security… much like the use of a drug, or another addictive behavior, provides a sense of relief or comfort or security to the person struggling with an addiction. And if our codependency is severe, the enabling behaviors really are addictive. We may feel restless or anxious if we are unable to enable, if our enabling is rejected, or if our enabling behavior does not have the desired effect. That feeling is not unlike the feeling of withdrawal someone struggling with drug addiction experiences, because it is impacting the same neural pathways in our brains.

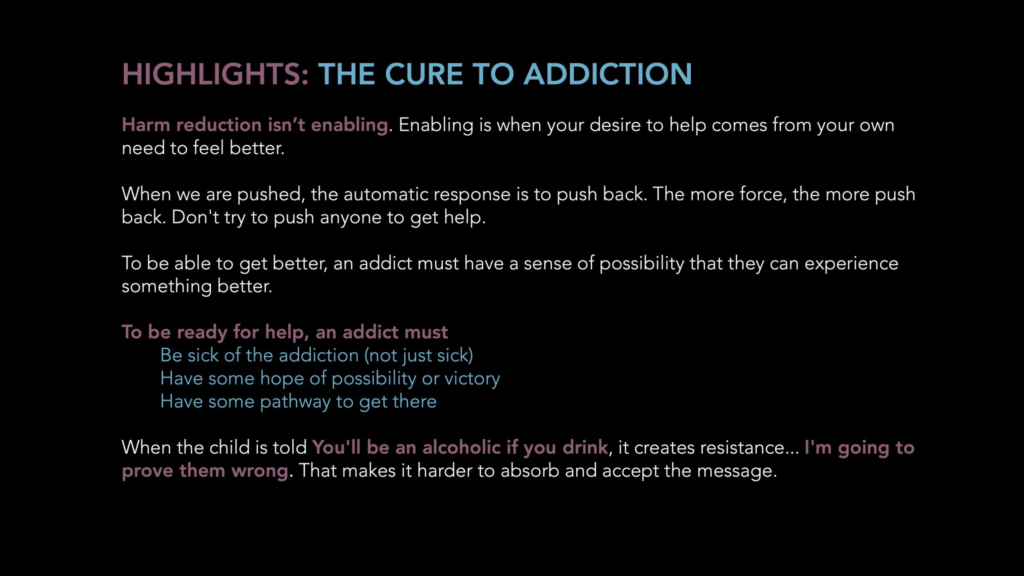

Why harm reduction isn’t enabling. Contrast this with harm reduction. First, harm reduction is generally provided by someone who does not have a direct benefit from the action. Second, there’s no emotional attachment to the outcome. Which is related to the third aspect: there’s absolutely no judgment. When we are working with harm reduction, we’re saying “ I accept you exactly as you are.” We don’t ask them to change. We don’t tell them what they should or should not do. We don’t judge them for the decisions they are making, and we don’t set expectations.

We are, in effect, saying “Here’s something that might be helpful. It’s up to you if you want to make use of it. I won’t judge you whatever choice you make. I’ll recognize and appreciate your ability to make the decisions that are right for you.” We don’t have to agree that someone is making the best choice; we simply don’t judge either them or their decision.

So when we’re operating from a mindset of harm reduction, we have no attachment to what happens. Of course, we hope this person will be happy and benefit from what we’re offering. But it doesn’t upset us, or create anxiety, grief, or stress if they choose not to do so. We are simply there, offering our support, without conditions or expectations. Again, for the person struggling with codependency, this may seem almost impossible. We enable because we’re driven by our own need to feel better. We need the other person to feel better, so we feel OK.

Listening to someone’s story is not enabling. As part of being unconditionally supportive, we can listen and be present and respect what our loved ones tell us. It isn’t enabling to hear them, listen without judgment, and help them to feel heard and understood. We don’t have to agree with what they are telling us. (And we don’t need to tell them we disagree, either.) But when we listen without agenda or judgment, what we’re doing is showing our loved ones the respect and regard for them and their experience. We are sharing curiosity and possibility with them. We’re giving them the chance to feel like their story matters.

Letting go of enabling and practicing unconditional positive regard. When we are able to let go of enabling and instead, show up for our loved one with unconditional positive regard, we help our loved one immeasurably. Our unconditional acceptance may trigger development of new brain pathways that help the person heal. It will definitely help change their self-concept.

When we demonstrate to our loved ones that we believe in them, and we see and believe in what’s possible for them, we create a sense of hope in them. When we communicate to our loved one that we trust in his or her ability to make the choice that’s best for them, we begin to instill confidence. Our loved one can build capacity for autonomy. Our loved one’s ability to believe in him or herself is absolutely core to being able to let go of the addictive behavior.

One of the most common questions from family members and loved ones of someone struggling with addiction is “How can I get my loved one to get help?” The short answer is, no one can be forced to accept help if they aren’t open to it. So what do we do?

Perhaps we must first understand what’s going on with the person struggling with the addiction. As Gabor’s mantra says, “The question isn’t ‘why the addiction’ but ‘why the pain.’ So we need to recognize that no one wants to be addicted. What anyone with an addictive behavior is after is not the addiction itself, but the immediate reward.

According to Gabor, the immediate reward is always, in some way, taking away pain. Maybe that’s physical pain, or (more likely) it’s emotional pain: anxiety, depression, anger. Sometimes the pain is boredom or lack of connection or love. Or maybe it’s some other type of pain. So, to be ready for recovery, the current remedy they’re using for their pain probably isn’t effective (or as effective) as it was. Or, perhaps, the side effects or other costs of the current remedy are no longer acceptable. In any case, what it boils down to is the pain of staying where they are is greater than the fear of doing something different.

Pushing someone doesn’t work. As much as we might wish that we could twist our loved ones arms to be ready for recovery, it rarely is successful. In the video segment for this lesson, Gabor demonstrates what happens when someone pushes against our hand. We resist. It isn’t even conscious; it’s a built-in response. In the demonstration Gabor give, we could simply drop our hand down and not participate, but we aren’t wired to behave that way.

Now, when we are concerned about our loved one making what we believe to be bad choices, or taking risks, our natural tendency is to want to stop them. But if we push our agenda, it’s no different than Gabor pushing an audience member’s hand: Our loved one will resist. They’ll push back. Or they’ll get angry and pull away.

The same is often true in the ways we try to control our children’s use of alcohol or drugs. Telling them “You’ll become an alcoholic if you drink” is not likely to work. Instead, it’s likely to trigger resentment and resistance. The child is more likely to want to prove you wrong.

In both of these cases, when instead of pushing, we instead invite them to join us, to have an honest conversation and we listen to them, and they to us, we have better results. And again, Gabor tells us that the essential condition for success in recovery is the presence of someone who cares about us, who will share unconditional positive regard with us. That’s really the most we can do for anyone else.

Of course, this doesn’t mean letting your loved one walk all over you. Pushing someone isn’t the same as setting boundaries. We probably won’t be effective if we try to control someone (especially if the person is an adult) if we say “I forbid you to drink.” But we can set a boundary and say “This is my house, and so I get to set the rules here. You don’t have to follow my rules, but if you choose not to, then you are also choosing to live somewhere else. If you’re going to live here, then I need you to follow my rules.” That isn’t pushing, and it isn’t controlling them (unless they genuinely have no other option and no way to be able to move out. That situation is more complicated, and may require the help of a therapist to cultivate effective boundaries.)

For the person ready to accept help, what are some of the factors needed to help the person struggling with addiction find recovery?

A sense of possibility is crucial. As we’ve discussed earlier in this course, the role of shame for our loved one is often what gets in the way. It’s hard to believe we can succeed if we’re holding on to the idea that we can’t get better, can’t stay in recovery, or aren’t strong enough. So one of the most powerful ways we help our loved ones is to help them see the possibility. As Gabor puts it, It’s not having hope; it’s that actually seeing possibility, and being the mirror in which our loved one can look at themselves and see the possibility of recovery and renewal.”

A sense of hope. Our loved one needs some taste of success, or, at the least, a clear awareness that others hold the belief that change is possible. This is different from possibility; here’s it’s finding confidence that we can be successful. The ability to find ourselves again. The ability to know what victory feels like, and understand it’s better than defeat.

Someone who believes in them is crucial. Not just hope, but genuinely seeing the possibility in them. For the loved ones of the person struggling with addiction, this is where our compassion, acceptance, and unconditional positive regard come into play. When our loved one feels and believes in success, and knows that others believe in them, it fuels a sense of confidence that drives the desire to succeed.

A pathway to success. For our loved one who may have tried over and over, they may simply not see the pathway out of their situation. Most of us who have addictions are lacking in some basic skills. We may not have much capacity to manage emotional discomfort, or take on new and potentially stressful endeavors. So having someone who can help to guide us, help us to see options is crucial. To succeed in the long term, we’ve got to learn how to navigate these situations, and that’s where having someone to help us map out a strategy will make a huge difference in our success.

There are many different approaches to treatment. Unfortunately, many are not rooted in proven, evidence-based practices. Many treatment programs and professionals tend to rely on “what worked for them”, which may not be the most effective treatment for someone else.

Gabor’s approach to addiction is part of an emerging awareness of trauma that has come about in the past 10 years. It is only in this relatively recent timeframe that the research on addiction has become more clear. This is in large part due to the Adverse Childhood Experiences studies referenced in an earlier lesson, but also to other advancements.

Of course, almost anyone seeking to attain and maintain long-term recovery will benefit from psychotherapy. One of the challenges for those with addiction and underlying traumas is finding a therapist who is adequately prepared to work with a client experiencing severe depression, despair, or uncomfortable emotions. While this sounds like it would be one of the most basic aspects of any psychotherapeutic work, many therapists are uncomfortable working in these deep places. This has to do with their own unhealed wounds.

This is not to say that therapy isn’t beneficial, or that any therapist cannot be helpful to those of us in need of help. What is true is that the deeper the therapist is comfortable taking us into our own wounds, the more fully we are able to understand and resolve the issues that lie at the core of our wounds and, thus, our addiction.

Finding effective treatment isn’t easy, but there are some specific approaches that are especially effective in working with the traumas that underlie addiction, and the therapists trained in these modalities are more likely to be familiar with the kind of deep work that is most beneficial for those of us seeking help with our addictive behaviors:

Internal Family Systems (IFS) IFS is a paradigm that looks at our mind and our selves as comprised of various parts, each of which has its own voice and perspective. In IFS work, the practitioner helps the client to talk to the different parts of self, that may have different perspectives, beliefs, and emotions. It’s a way of safely and effectively getting to the unconscious beliefs that limit us or sabotage us. The IFS institute (ifs-institute.com ) has a referral network of therapists trained in using this modality. Gabor uses pieces of IFS in the work he demonstrates in this course.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) EMDR is a specific intervention developed to reduce the distress associated with traumatic memories. The name is a little bit of a misnomer, as EMDR was once practiced solely by directing the client to move their eyes in particular ways. Today, EMDR is practiced using binaural sounds in headphones, by tapping fingers, and by other means. While it sounds unlikely, it is one of the most well-established and widely studied forms of trauma treatment. EMDR has been used in Veterans Administration hospitals for more than three decades and is one of the most effective means of helping clients with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). When practiced by a therapist or professional trained EMDR, it is safe and effective at eliminating the emotions and discomfort associated with traumatic memories. The EMDR International Association (emdria.org) has a referral network of professionals trained in using this modality.

Somatic Experiencing (SE) SE is a means of working with a client’s perceived body sensations (somatic experiences) and integrating them with memories and experiences. It differs from other approaches in that it integrates body experiences with memories. Those who work with SE help clients move beyond the thinking aspect of understanding traumas. SE basically reprograms our body’s most basic survival instincts. When practiced by a trained SE practitioner, the client is able to integrate body and mind in a way they may have been unable to previously experience. This can provide a greater sense of connection to the body, and cultivating a state of safety and comfort. The Ergos Institute of Somatic Education (somaticexperiencing.com) has a referral network of professionals trained in using this modality.

Trauma-Informed Yoga (TIY) shares some similarity with somatic experiencing in that both are looking at the entirety of body and mind. TIY treats trauma as something that affects both body and mind. It looks at the imprint of the trauma that has impacted body as well as mind. Since trauma involves threats to survival, there are elements of those threats that remain imprinted on the bod. This results in trauma to the body and imbalance to the nervous system. TIY helps to bring the nervous system back into balance. It uses gentle movements and poses that soothe and bring balance to the body and nervous system, and integrate the body’s experience into the mind. The body-based approach can assist the individual in integrating experiences between body and mind, safely helping the client release the emotions and stresses associated with the trauma experience.

Mindfulness Meditation (MM) is a means of training and focusing your attention on the current moment, helping you to reach a state of concentrated calm. In MM, students are taught to bring their awareness to a place of gentle focus and peace, where you slow down your thoughts and release unwanted emotions. This brings a state of calm to your mind. It is usually a practice involving focused breathing combined with awareness. The student learns to simply allow thoughts to pass through and be released. There are many different types of MM, the most widely known of which is Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. The benefits of MM are well documented, and are valuable means of helping rebuild the deficient brain pathways and brain chemicals. MM has been shown to reduce cravings and also to help with many mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, anger management, and others.

Medication Assisted Treatment is extremely effective for many clients.

Medication-assisted treatment (or MAT, as it is known) is becoming increasingly common, especially for those of us with narcotic use disorders. MAT has been a literal lifesaver for many individuals who had, prior to MAT, relapsed and been back to treatment many times.

What MAT does is supply the brain with the deficient brain chemicals that would otherwise create the cravings for drugs of abuse. While it does not heal the brain chemical deficiency, it is very effective in keeping people off of the self-administered drugs that carry risks of overdose, increasing tolerance, impurity and drug potency problems, and other risks of illicit drug use.

There is a common misconception that those of us who are on medication-assisted treatment, such as methadone or Suboxone or Vivitrol are “not really sober” or that it’s “enabling.” That’s nonsense. Those of us who are candidates for MAT are already using narcotics. Most have failed in previous attempts to get off and stay off of narcotics. MAT takes away our cravings, while enabling us to function effectively in society.

Some of us may use MAT for a limited period of time, as a step toward abstinence while we’re doing other things to heal our brain circuits. For others, where it may be difficult to rebuild our brains to the point where we don’t have cravings, MAT may be an effective long-term solution. In either case, MAT allows us to function normally and effectively in society, and to live a productive life that we might not otherwise be able to do. In that way, it is really no different than insulin is for diabetics, or high blood pressure medication is for those with hypertension.