Codependency is, like triggers, perceptions, and just about every other part of ourselves, a function of what we learned as children. It has many facets, but a key part of it is a strategy of connecting our value or worth to what someone else does or doesn’t do. And co-dependency, as its name implies, requires two or more people. Typically, one is caretaker or ‘enabler’, the other is the dependent. Often, the roles between the two interchange. But it isn’t a one-way relationship; the enabler often gains a sense of worthiness, a means of control, or some other benefit, while the dependent is, in some way taken care of. It is rarely an effective relationship in the long term.

Codependency is a topic that has entire books written about it. Our discussion in this lesson is in the context of addiction and families, where codependency is nearly always present. But before we go further, note that codependent behaviors are learned from our parents and the environment we grow up in. Our parents, in turn, learned it from their parents. No one wakes up and decides to be codependent, and no one intends to behave that way. So let’s put aside any judgment or shame,

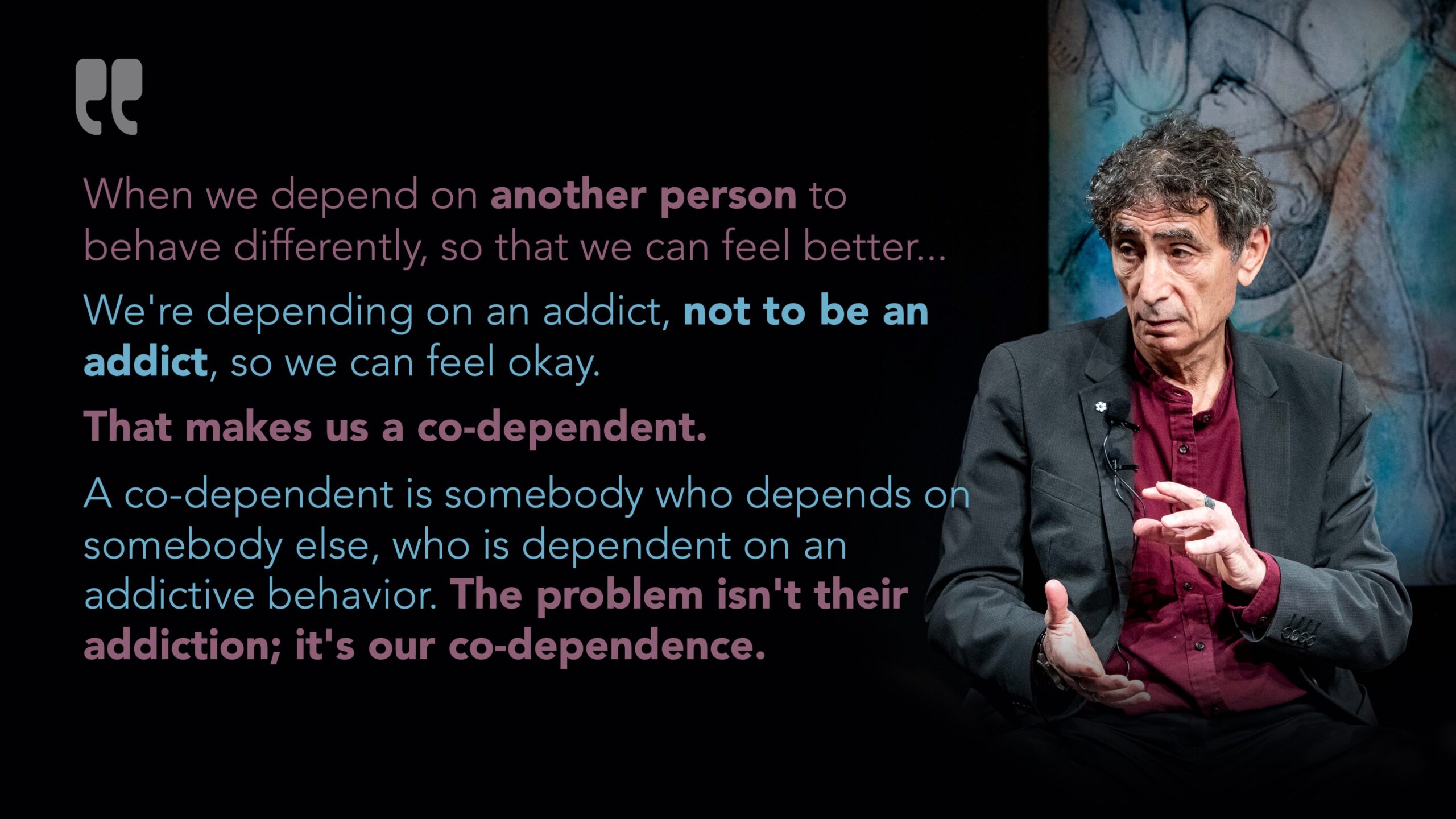

Regardless of whether we’re the dependent or the enabler, codependency interferes with autonomy. It makes it hard to think for yourself. It makes for blurred boundaries. And many people use the word in a way that’s dripping with judgment or accusation: “Stop being codependent.” “If you weren’t so codependent, I could just live my life.” But if we can view codependency through the lens that Gabor is showing us, we might see a different perspective.

Think about codependency, boundaries, and what we’ve already learned about perception. Codependency, whether we are enabler or dependent, is driven by perceptions that are filtered by our earlier-in-life experiences. It’s further complicated by the intertwined nature of the connection between the codependents. All of these pieces fit together.

In our addiction-affected families, we often hear from the enabling person “I have to save him” or “She needs my help” or “I can’t just let him be on the street” or something similar. Conversely, we hear from the dependent person “I wish she weren’t so controlling” or “I wish she’d leave me alone.” Of course, we hear the opposite messages as well: “Why won’t you do this for me”, or “I can’t take this anymore.” Codependency represents a constant struggle between competing desires and needs, which are rarely met. Everything comes with strings attached. Both parties struggle with resentments toward each other. Boundaries (on both sides) are rarely respected.

In short, nobody’s happy. And that’s because our unmet needs and our filtered perceptions are getting in the way. If we’re an enabler, we probably want to be loved and appreciated. Or to feel needed. Or to gain control, so we don’t feel out of control. If we’re a dependent, we probably aren’t good at asking for our needs. Or we don’t feel confident. Or we don’t feel lovable. (Yes, a lot of those “feels” are perceptions, not needs. They’re used here for language simplicity.)

So much of the web of codependency is driven by perception and unmet needs. Here’s the catch: Understanding it intellectually doesn’t mean we can just change our behavior. We’ve spent decades learning it. The underlying behaviors and perceptions allowed us to survive. So it will take time to learn new, more effective strategies.

One of the first things we can do is simply acknowledge our behaviors. Talk to the people we’re connected with. Have conversations about codependency. Own our own behaviors, and ask the other person to acknowledge theirs. Agree to gently, respectfully, and lovingly point out or remind each other when we’re acting with codependence.

And… we can give ourselves, and those around us, permission to be imperfect. To fail. To fall into old patterns. We can recognize that overcoming these behaviors is a practice. It’s not something we achieve and are done with. When we do that, it’s much easier to accomplish.

For those of us who are on the enabling end of the spectrum, it can be scary to let go. To step back, and to give up control, judgment, and expectation. But when we do this, often, something wonderful happens. The person we’ve been tangled up with suddenly feels the freedom of not being controlled. S/he doesn’t have to worry about disappointing you. There’s no fear about what happens if s/he fails. With the loss of that pressure, and those expectations, very often the person can now feel free to actually improve him or herself. Maybe they’ll ask for help from someone other than you. Maybe they’ll ask you, but in a different way.

And for those of us who are dependent, having boundaries, and letting go of the codependent support we may have relied on can also be freeing. We may suddenly feel our sense of worth improving. We might discover that we can now make our own decisions. Even if they aren’t perfect ones, we learn, and we can get better.

Nothing about this process is easy. But we can approach it with love, compassion, and non-judgment. Curiosity. An open mind. A recognition that no one is at fault, no one is to blame, no one is trying to harm the other person. With that perspective, we communicate better. We have clearer, more effective boundaries. We can find our worthiness within ourselves. And ultimately, that helps us live happier, healthier lives.