Lesson 1 of 0

In Progress

Lesson Two: A New Look at Addiction

In this lesson, we look at addiction and its impact on us, both individually and as part of a family or group of loved ones. As you go through this course, you’ll likely notice that we repeat certain themes and elements in different lessons. That’s intentional.

A lot of Gabor’s approach to addiction requires thinking about ourselves and our experiences differently than we have in the past. We reinforce points that are especially important so you’ll be sure to learn them.

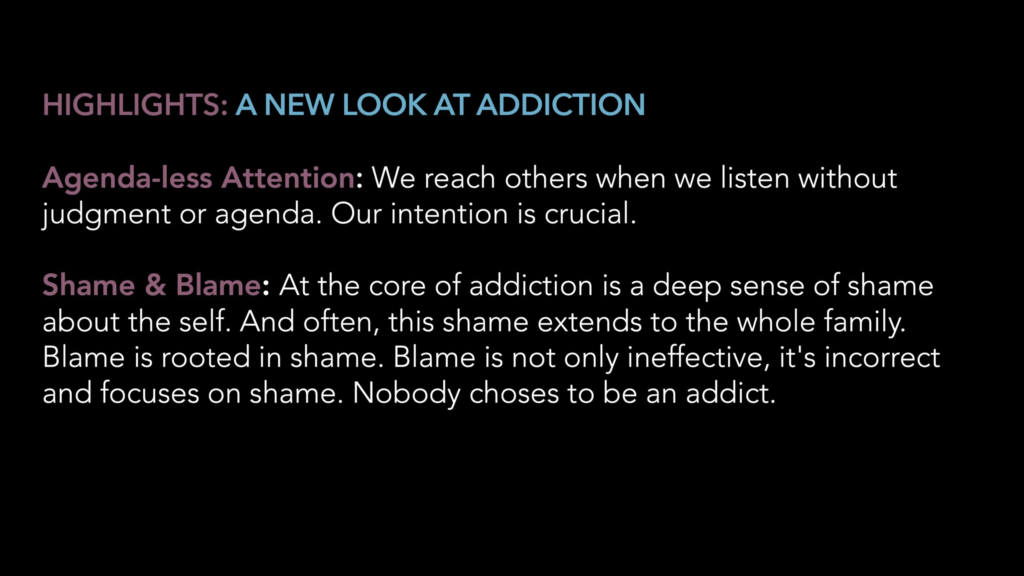

Our Tendency to Blame

Before we go any further, it’s worth revisiting this. In lesson one, we talked about letting go of blame. Blaming someone won’t help us solve any problems. It isn’t effective in improving communication, and it definitely doesn’t make anyone feel any better. It doesn’t encourage behavior change either. It just makes the blamed person feel bad. That’s true whether we are blaming ourselves or blaming someone else.

Gabor describes blame as showing up in two ways:

- We blame the other person

- Family members blaming the person with the addiction: “You’re creating these problems for us. Your behavior is imposing suffering on us and making our lives difficult.”

- The person with the addiction blaming the family: “You’re trying to control me. You don’t understand me. It’s because of what you did that I developed this addiction.”

- Blaming yourself:

- “I suck as a human being. I’ll never be able to stop judging my kid.”

- “I’m a terrible person. I’ve stolen and lied. No one will ever love me”

What lies underneath our blame is deep shame. That’s true whether we’re the person struggling with the addiction, or the family member affected by it. Shame is something everyone has, and research shows that the less we talk about it, the more we have it. But when we talk about it, we begin to heal it. We realize others have had the same experiences, or share the same worries or self-judgments that we have.

Even if we’re not ready to let go of the blame, Gabor suggests that when we interact with our loved ones that we set aside the blame. When we approach them with compassion and curiosity, we open the door to understanding and healing.

Listening Without Agenda or Expectation

Gabor suggests that the best way to improve communication is what he calls “Agendaless Listening.”

How often do we “tune out” part way through what someone is saying, so that we can begin to form our own response? How often do we try discussing an important topic, and feel that we aren’t being heard? Both of these are different types of “agendas” that get in the way of listening to another person.

With agendaless listening, we simply listen. Without judgment, without feeling defensive, without anger. We open our minds and our hearts. We do our best to discard any previous judgments or notions about what the other person might be “trying to do.” We simply, as Gabor puts it, “let them download whatever is on their mind” so that we can hear them and hopefully understand their perspective.

This doesn’t mean we have to agree with their perspective. But we can listen, hear their view, and do our best to understand what and how they are thinking. And perhaps we hear something we didn’t hear before. Or else, we understand why they believe what they do.

The Role of Shame

To be able to let our own guard down, we’ll need to look at the things that affect our beliefs, our perceptions, and how we think. As Gabor demonstrates, our first tendency is “shields up.” We defend ourselves. One of the ways we do that is by making assumptions, which are often wrong.

Yet those assumptions are rooted in painful experiences that have happened to us in the past. These experiences affect how we interpret what’s being said. In the first demonstration, Gabor speaks to two people who are each upset at a situation that’s occurred for them. In both cases, he demonstrates that their anger comes from choosing the conclusion that’s most painful to them, instead of another that might be a lot more sensible under the circumstances.

We choose the painful choice because of shame. All of us hold beliefs – mostly on an unconscious level – that we aren’t worthy of love, that we “aren’t enough,” that we’re an imposter. Nearly all of us hold these beliefs to some degree, and generally, the less we talk about it, the more we have it.

When we are feeling ashamed, we tend to protect and hide those parts of ourseives. This invites dishonesty and denial. Researchers on shame have found that when we communicate with others while feeling shame, we tend to do one of three things:

- move toward (pleasing behaviors)

- move against (get angry; come out swinging; say hurtful things)

- move away (shrink down and try to disappear.

And, of course, we may lie, misrepresent, avoid, or deny the truth, because it’s too painful. Most of us do a combination of these things, but none of them are helpful.

Shame impacts people in the addicted family in different ways:

- The person living with the addiction may feel shame that he’s letting everyone down, or that he can’t control his behavior, or that he doesn’t deserve the chances he’s been given, or that he’s a bad person because of the decisions he’s made.

- The family member may feel like the addicted family member’s addiction is their fault. Or feel like they’ve failed because they “haven’t done enough” Or they blame and feel shame for behaviors and decisions they may have made years ago that had a negative impact.

The key to understanding and letting go of shame is recognizing that all of us, very early in life, learned behaviors that helped us to survive. This might have included pleasing others, not asking for our own needs, or seeking attention. All of those are helpful in some ways, and not helpful in others.

But the important thing is, those behaviors were necessary at the time. Without them, we would have lost attachment, and as young children, we could not have survived. We are not bad people because of the behaviors we’ve learned for survival. And it takes time to “unlearn” those behaviors, even if we’re working hard on it.

We let go of the shame by accepting our faults. By acknowledging we could have done better, and we’re going to do our best to do so going forward. By being honest when we screw up. By giving ourselves permission to screw up. By talking about the shame we feel.

When we do this, we let go of shame. We act authentically. We take responsibility for our actions. We seek to do better. And when others in our circle of family or loved ones see this, often they will begin to do the same.

That comes from our past traumas. Understanding our traumas is a crucial part of understanding addiction (as well as family communications). So we’ll be covering that more in the next unit. For now, all you need to know is that we behave, say, and do things in large part because of strategies we learned very early in life. And those strategies were, at one point, helpful and effective for us, even if they aren’t any longer.

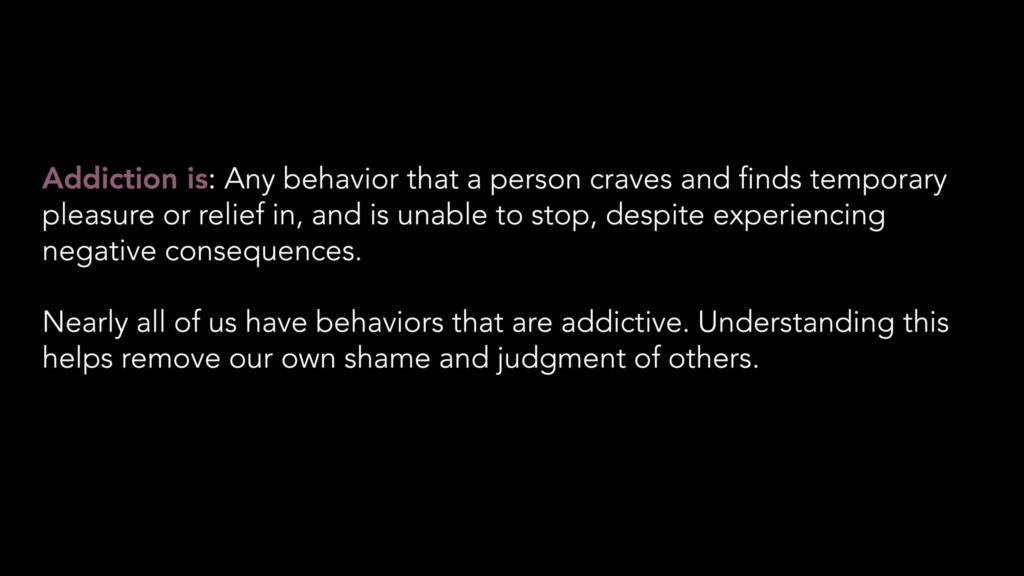

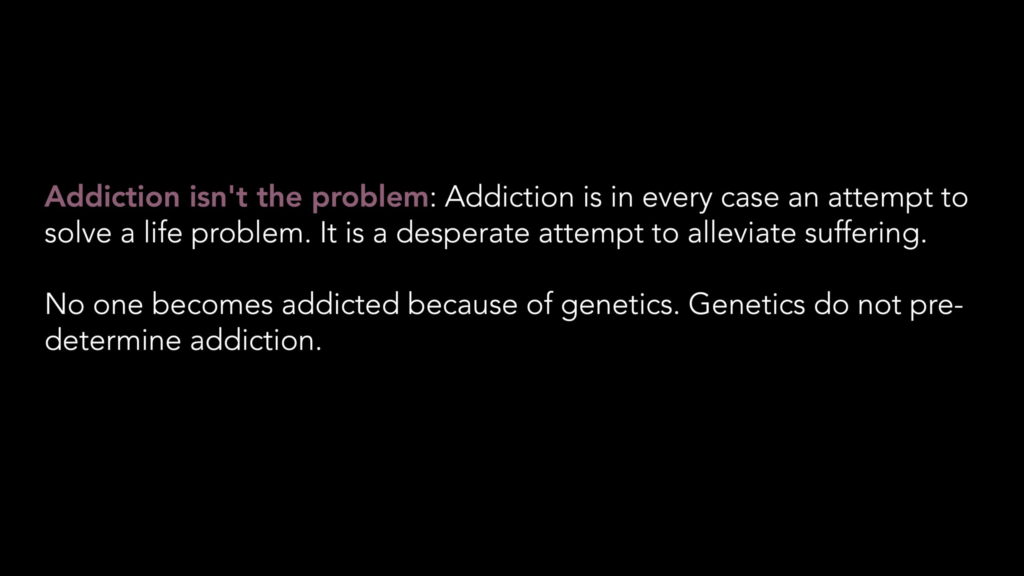

A New Perspective on Addiction

Gabor’s research and his experience as a doctor has shown him that addiction is not a brain disease. It is not genetic, though we may have genetic traits that increase our risk for addiction. It isn’t a choice (that’s the one that so many people have difficulty understanding.)

So what is it? Gabor sees addiction as complex set of behaviors and experiences. It gives us pleasure, relief, and cravings in the short term. In the long term, it’s something we can’t or aren’t ready to give up, in spite of the bad things that happen to us as a result of our behavior. But that’s just a definition. To better understand it, we have to look at why we’re seeking the pleasure or relief. And that ties back into shame. It’s a loop that feeds into itself.

What I mean by that is, the drug or behavior we’re using is something that gets us out of pain. Maybe the pain is boredom, or depression, or anxiety. Or a feeling that we aren’t loveable. Or a belief that no one will like us if they see “who we really are.” Or the pain of not being comfortable at a party with friends. Or perhaps the drug simply gives us joy and pleasure that we’re lacking.

All of those are reasonable things that just about everyone wants. But for those of us with addictions, our brains didn’t develop for us to be able to experience those things the way “normies” do, in large part because of the experiences we’ve had in our families of origin.

(And, just as a reminder, this isn’t anyone’s fault; as parents, we give our children the best we can, but our ability to do that is limited by our own wounds. And many of us, parents or children, aren’t really aware of the wounds we carry until we take the time to look for them.)

So someone who is addicted simply has a brain that’s wired differently, because it didn’t get the stimulation that cultivated healthy brain function. And for us, the first time we used alcohol, or a drug of abuse… it probably felt wonderful. It made us able to feel all the things that everyone else can feel all the time. So when you think about it, who would want to turn that down? Who would want to stop doing that? Who wouldn’t want to do that compulsively?

Hopefully this is beginning to make a little more sense now. Those of us struggling with addiction, the things we use that make us feel good started out by making our brains feel things we’ve always wanted to be able to feel, but maybe we didn’t know it was possible. Because our brains didn’t develop with the brain chemical “factories” and “highways” (as we talked about in the last chapter). And that’s why it’s not a disease, and not a choice.

The genetics is more complicated to explain, but in brief, no gene has been found that is conclusively linked to addiction, and even if there were one, it would not explain the huge increase in addiction. Our brains simply don’t evolve that sort of change over a decade or two.

There are genes that, if present, make us more sensitive. So people with high sensitivity are more likely to want to use something to numb down those feelings. But that isn’t a cause of addiction; it’s, again, a pain, a discomfort that the behavior seeks to get away from.