Lesson 1 of 0

In Progress

Lesson Three: Exploring Our Trauma

In this lesson, we begin to explore trauma and how it affects us. By “us,” we mean not just the person struggling with addiction, but that person’s loved ones. And by “trauma,” we’re referring in particular to traumas that happened to us early in life.

Understanding Childhood Trauma

Trauma is a wound that happens to us. It can be physical, emotional, or both, but when we’re talking about it in this course, we’re speaking mostly of the emotional impact. Trauma has an especially strong impact on us when we’re young. Something that might not matter to us as an adult can have a huge impact on us when we’re children. Experts who study childhood trauma think of it in two categories, “Big-T” and “Small-t”.

Big-T trauma

Big-T trauma is usually one or more major events where we feel loss of control. Some examples:

- Sexual or physical abuse

- Injury or illness requiring hospitalization

- Loss of a loved one

- Breakup of a family

- Domestic violence in the home

There are many types of big-T trauma. And it isn’t just trauma that happens to us, but trauma we are around and observe. This includes things like growing up with a parent who is always angry, not having adequate food or shelter, watching parents fight, or seeing someone harmed.

Small-t trauma

Small-t trauma is the build-up of smaller events that happen over and over. It feels like “death by a thousand paper cuts.” Some examples:

- Bullying

- Having our needs minimized or ignored

- Criticism or mocking of our behaviors

- Being told we’re too fat, thin, tall, short, unattractive

- Being made fun of

- Good things that should have happened but didn’t.

We often experience a series events that don’t seem like a big deal, where we felt devalued, unloved, or our needs weren’t met. Though the events may seem trivial to our adult selves, they are often painful to us as children.

How trauma affects us

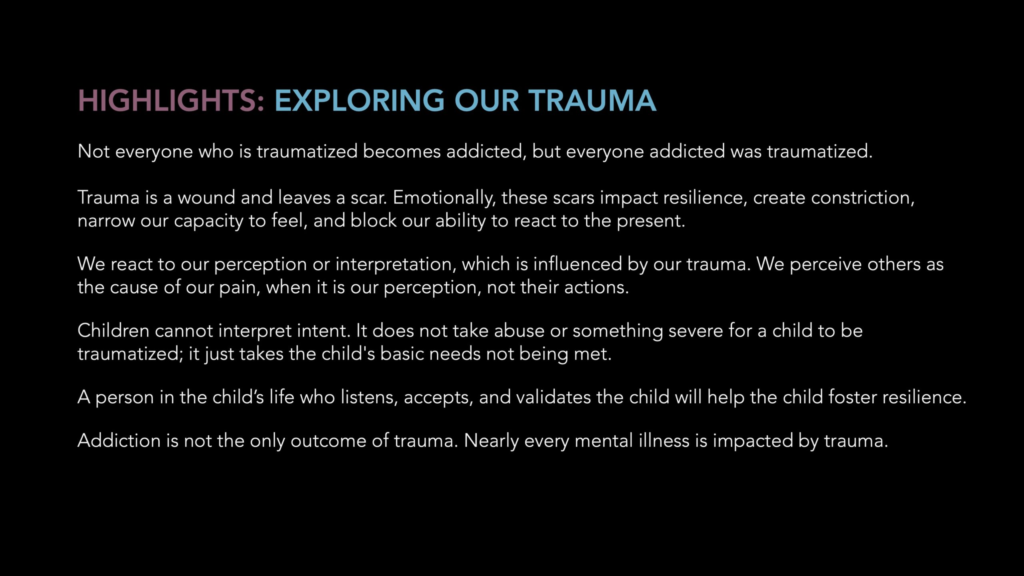

It doesn’t matter if it is big-T or small-t trauma. When we’re constantly devalued or unable to get our needs met as a child, we feel traumatized. But trauma does not, by itself, cause serious harm.

That is a really important difference.

If we felt unloved or bullied or ridiculed, but had someone we talked to … someone who was safe, who would listen, who wouldn’t judge us, who helped us understand what happened… then we’re less likely to be negatively affected. Being validated and listened to makes all the difference. We don’t feel so alone, we know there’s someone who understands.

On the other hand, if we had those same things happening… feeling judged or dismissed or unloved or bullied, but we didn’t have anyone we felt safe telling what happened, then we were likely traumatized. Or, perhaps we told someone, but they didn’t believe us, or they minimized what happened, or just told us to “tough it out”. That’s just as damaging, and maybe more damaging, than if we didn’t have anyone to tell.

As children, we’re wired to seek connection to keep us safe. We know, instinctively, that we can’t protect ourselves, so we rely on parents or other adults to protect us. We’re hard wired to look for that. If we don’t get it, not only is it traumatizing, it actually impacts how our brain develops.

If we don’t feel that protection, our brain pathways will develop “out of balance.” The pathways that manage “fight or flight” will over-develop, and the pathways that let us feel protected and safe won’t develop much at all. This doesn’t necessarily mean we’ll become addicted to drugs or alcohol, but we will learn to compensate in some way. We’ll probably also be at greater risk of developing an addiction.

It’s probably becoming clear now that trauma, to a large extent, comes from a lack of emotional connection. We don’t feel heard. We aren’t getting our needs met. We don’t believe that we matter. It doesn’t matter if that’s objectively true. All that matters is that as children we believed it, and integrated that belief into how we define ourselves.

A brief reminder about blame and shame

Reading the above, it’s easy, as a parent, to realize where we failed. Maybe we worked too much when our children were small. Or maybe we were short-tempered. Or depressed. Or maybe we judged our kids really harshly. Or didn’t show enough affection. Or perhaps something else.

As Gabor says, “If you’re worried about whether you screwed up your kids, don’t worry. You did.”

What he means by that is, no parent is ever perfect. We are at least partly byproduct of what we experienced growing up. Nearly all of us had experiences that were traumatizing, and most of us, at least some of the time, had parents who missed the mark. Maybe a little, maybe a whole lot.

So how we “show up” as parents is, to some extent, a result of what we experienced as kids. Even when we’ve had therapy, or “done our work” or tried our hardest. No one can ever do a perfect job. What we can do is to try our best to let go of any self-blame or judgment, and do our best going forward.

The same is true for those of us struggling with addiction. We are the product of the experiences we’ve had. That, in turn, affected how our brains developed. It isn’t helpful to blame anyone for where we are in life. Nor should we blame ourselves, even if achieving recovery has been a challenge. When we accept and love ourselves exactly as we are, we begin to ‘rewire’ our brains and are on the path to recovery.

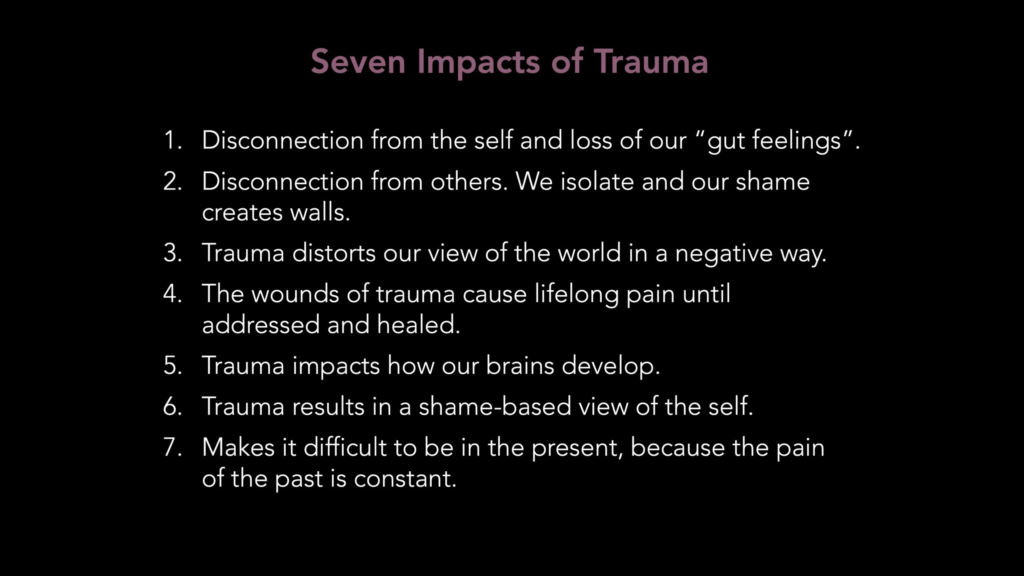

Gabor describes seven ways in which trauma impacts us:

- Separation from self. We lose touch with our intuition.

- Disconnection from others. It’s hard for us to trust and to connect with those around us, and we feel lonely or isolated.

- The world is distorted in a negative way. We see the world as dangerous and untrustworthy.

- Creates a wound that never heals. Trauma creates emotional pain that we need to escape from. The pain is there until we work through it.

- Impacts brain development. It influences our ability to feel emotions, our impulse control, and other factors.

- Creates shame-based view of self. We think of ourselves as unworthy of love, belonging, and success.

- Makes it difficult to be in present moment. We respond to situations that remind us of the past, rather than what’s happening in the present.

The Effect of Trauma on Behavior and Communication

We’re wired to learn from the world around us. This is especially true when we are young children, because our brains are absorbing our experiences. This is how we learn to make sense of the world.

But what happens if the world around us isn’t safe? What if we’re told (with words or actions) that our needs aren’t important? What if the protection we’re wired to seek isn’t there? Our young brains learn to adapt, so that we can survive. We become very aware of our environment. We’re always on the lookout for danger. We aren’t able to experience calm, joy, happiness because those parts of our brain weren’t developed.

So when we grow up, our brains are wired by our experiences. And that affects how we act. We assume people won’t be there for us, or aren’t trustworthy, or that our needs won’t be met. Maybe we stop asking for anything, because we’ve been trained that we won’t get it. Or maybe it’s the opposite: we seek attention and act out, because that’s what we learned was effective. There are lots of other behaviors and protections that we may have learned in order to survive.

And so, because of our traumas, it’s hard to be present in the current moment. When we experience something in the present, our brains are wired to respond to something similar that happened in the past. A “story we make up” that isn’t actually true, but, in the moment, seems very real. Some examples:

- People aren’t trustworthy, so anyone I date will eventually break up with me. I’d better push them away first so I don’t get hurt.

- I’m not worthy of anything good, so I won’t be successful at whatever I’m trying.

- Anything good will get taken away, so I will sabotage it first, so I don’t get hurt.

That compliment wasn’t real. It was said to manipulate me, so I can’t accept it.

The Role of Connection

Ultimately, trauma – or more precisely, the negative effects that we experience from trauma – arises largely from a lack of emotional connection. So whether we’re trying to prevent the harm that’s come from trauma, or overcome the impact trauma has caused, the most effective strategy is the same: We create and nurture safe, attuned connection with others.

Healing trauma. The impact of trauma on the brain comes from a lack of connection. The neural pathways we need didn’t develop. The good news is, we now understand that the brain is capable of building new pathways and reinforcing existing ones throughout our lives.

Simply by having meaningful conversations with people, we develop and strengthen these pathways. Listening to others share their stories, their successes and failures, and connecting with them is one of the most powerful ways we have to heal our brains. Authentically sharing our own story, and having someone sit with us, hear our story, and validate our experience helps our brains attune to others. Both of these rebuild or enhance the neural pathways that are deficient.

Building resilience. We can’t keep our children from being traumatized. No matter how protective we are, kids or teachers or friends say mean things. Some kids get bullied. Others, for whatever reason, have difficulty making friends. We might be distracted or upset and say something thoughtless. These experiences are part of nearly everyone’s childhood. But these traumas do not have to impact our children, or put them at risk of addiction or other difficulties.

We can start, today, to build resilience in our children. First, we can listen without judgment. We can look at our own wounds or experiences, and what unconscious messages we might be sending, and do our best to change that. We can encourage our kids to be open and honest by validating their feelings, never minimizing or ignoring them. We can practice unconditional positive regard. (Never easy, but incredibly beneficial to the child.)

And if there’s a child in our lives that maybe doesn’t have someone who can listen and validate and be there for them, maybe we can be that person.

Exercise: Building Attunement

The next time you find yourself upset about something, give it an hour or two after it happens, and then do the following:

- Write down, as objectively as you can, what happened,

- Try to step back and ask yourself, “what was my emotional reaction?” (Be sure to separate perception from feeling. Feelings are mad, sad, glad, afraid.)

- Ask yourself “What was the hurt and pain about?”

- Ask yourself, “Are there other possibilities other than the first one I came up with?”

- Is this the first time you’ve felt this experience (feeling this emotion)?

- If not, what can I remember about the first time I felt it?

- What went on back then? Can I see it with a different perspective?

Doing this once a week will help you work out your trauma. You’ll get more distance from the trauma, and in time, you’ll find yourself getting less upset, less often.