Lesson 1 of 0

In Progress

Lesson Six: Addiction: A Disease or a Developmental Condition?

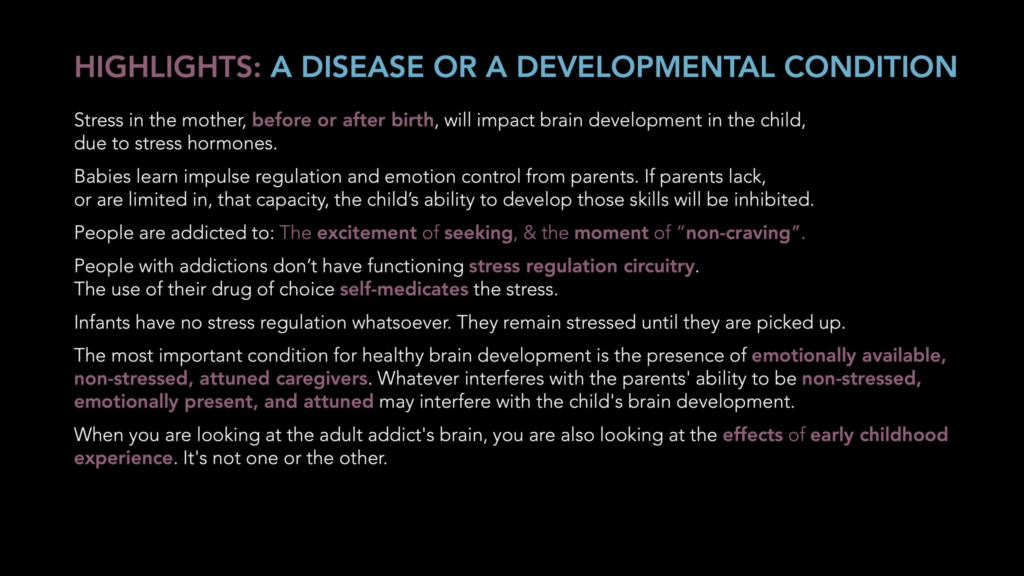

In Lesson Six, we expand discussion on how the desire to self-medicate discomfort drives addiction. We explore how early childhood experiences affect the development of impulse control and brain pathways that drive addictive behaviors. We then discuss how we break the cycle of addiction as it is passed down through families.

Much of what you read or learn about addiction will tell you it is a disease. Gabor’s decades of experience and careful study of the research shows otherwise. Now… to be clear, saying it isn’t a disease does not mean it’s a choice. It isn’t. Nor does it mean it is easy to treat and overcome. Anyone who has struggled to overcome an addiction knows how difficult it is.

The popular view has been that it is genetic. It can look that way; addiction is almost always seen to occur in families, passed down from parent to child. But here’s the problem with that: Genes don’t change very quickly, certainly not in one or two generations. And the incidence of addiction, especially to opiates, has skyrocketed in the past 20 years. Way, way too quickly for it to be genetic.

As for the “disease” idea, well… addiction is typically described as ‘chronic, progressive, and fatal if left unchecked.’ But that isn’t actually true. It is not the addiction itself that is progressive and fatal. It is typically the impact of the drug that goes hand-in-hand with the addiction that causes the progression and mortality. For example, when we look at video game addiction, or porn addiction, or even marijuana addiction (which is quickly increasing), we typically don’t hear of people dying from those. There’s no inherent biological degenerative pattern from the addiction itself. The degeneration happens as a result of the drug or behavior that results from the addiction.

So what if, rather than a disease, addiction is instead a disorder? A dysfunction in the brain, that originates as a combination of biology, psychological factors, and social factors? This is a whole lot more consistent with what we know about addiction, and greatly impacts the effectiveness in treating addiction. The following section explains, more sensibly than the genetic explanation, why it is handed down through families.

In previous lessons, we have discussed how early childhood experiences influence and impact our behavior, our beliefs, and our perceptions. Now, let’s take a look at how these experiences influence our brains and bodies.

Before we’re born, when we’re in our mother’s womb, the development of our infant brain is influenced by the hormones in our mother’s body. If our mother has a calm, non-eventful pregnancy, then our brain develops normally. But if mom is stressed, depressed, anxious, or has other mental health challenges, our brain might not develop normally. This is true whether the stress is internal (such as a mother with mental health or addiction issues) or external (stresses from a job, environment, unstable housing, domestic violence, being a single parent, for example.) Stress hormones from our mother’s body will influence the development of the neural pathways in our infant brain. We don’t develop the normal calming neural pathways in our brain. Dopamine, endorphin, and serotonin (brain chemicals called ‘neurotransmitters’) can be affected.

This is also why adopted children have a higher risk of addiction, suicide, ADHD, and other mental health disorders. By definition, any woman that is giving up a baby for adoption is stressed that she’s having to give up the baby. That’s going to have an impact on that baby’s brain development. Additionally, as we develop in our mother’s womb, our entire environment and everything we experience is directly connected to our mother’s body and presence. From her voice to her heartbeat. It’s all we know. When we are separated from our birth mother, we experience trauma and that impacts our development at a critical time.

Remember the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, from an earlier lesson? Those adverse experiences impact how our brain develops. And as mentioned above, adverse experiences to our mother when we’re still in the womb also impact our brain development. These experiences impact how our brain develops, and how the brain chemicals and pathways develop.

When this happens, we don’t get the normal “highway” sized pathways and free flow of brain chemicals in our brains. The flow is limited, because the pathways don’t develop correctly. This brain chemical deficiency limits our ability to feel connection and happiness. We can’t feel alive and interested and motivated the way we as humas are supposed to feel. But when we use drugs or alcohol, we artificially stimulate release of the deficient brain chemicals. So often, what we feel from using drugs is what non-addicted people feel naturally. Does it make sense why that feeling is addictive? Who wouldn’t want to feel normal?

Now addictive behaviors aren’t limited to drugs and alcohol. When we play a fun video game, or go skydiving, or buy something we want, or some other exciting activity, that stimulates some of the same brain chemicals, especially dopamine. Lots of things can do that, including sex, food, shopping, gambling. And that’s why all of those things can, for some people, be addictive as well.

The challenge with drugs of abuse is just how much they stimulate the release of dopamine. For example, eating a favorite meal fires dopamine, giving us pleasure and satisfaction. Skydiving might be twice the dopamine “hit” as the meal. But a hit of crystal meth produces about 1200% of the amount of dopamine that eating the meal does. Other drugs of abuse are similar. And that is why they’re so addictive. Drugs of abuse have similar impact on other neurotransmitters as well. Serotonin is known most for its impact on mood, and some drugs of abuse dramatically increase (temporarily) serotonin availability. Endorphins impact our sense of connection and love, and some drugs of abuse, especially opiates, are so powerful that they are described as “a warm, soft hug.”

A healthy person’s brain has a normalized flow of these neurotransmitters, so the drugs of abuse don’t have nearly as much effect on them. That’s why the majority of people can abuse alcohol, say while in college, but not develop a long-term problem with alcohol use disorder. The same with people who are prescribed a powerful opiate such as morphine or Oxycontin after surgery or an injury, and have no problem coming off of it when they are better.

But the people whose brains did not develop properly in childhood will have a different experience: They will immediately feel a sense of normalcy that they’ve never felt. That is what makes these drugs so addictive. Add on top of that the impact of traumas, which could be memories, or mental health disorders such as anxiety or depression. Or perhaps there’s resulting pain or empty feelings that result from that. The individual with that kind of history may seek out the use of drugs or alcohol to numb or decrease the pain.

Not everyone uses drugs of abuse to boost the flow of brain chemicals through their deficient brain pathways. As we mentioned above, some achieve this with other addictive behaviors, like gambling, shopping, sex, video gaming, exercise, or “adrenalin junkie” activities. Still others will numb their discomfort by immersing themselves in work. Others will find ways of tuning out; ADHD is the byproduct of tuning out, for example.

There are many different ways in which our childhood experiences influence our brain development and mental health. And just as many ways in which we cope with those aftereffects.

Babies can intuitively sense the emotions of their caregiving parents. It’s a survival skill that enables us, before we can talk, to understand those who are caring for us. This is important because when we’re born, we have no capacity to manage stress regulation whatsoever. If we are stressed because we need food or attention, we remain stressed until we are picked up and cared for by our caregiving parent.

We learn to control impulsive thoughts and manage stress by what we observe and intuit from our caregiving parents. What happens, though, if our caregiving parents aren’t good at managing their emotions, or regulating impulsive thoughts and behaviors? Well, without having an effective role model, we don’t effectively learn these skills. We may learn their dysfunctional strategies for handling stress. Or we develop our own strategies.

In most cases, the strategies we learn, without good role modeling, are ineffective. They may work in the short term, but they aren’t helpful in the long term. Maybe it’s depressing our needs and our feelings. Or being overly pleasing to others to charm them into giving us what we need. Or becoming angry and acting out, because that way we get attention. Or burying ourselves in work or video games so we don’t have to think.

Or… maybe we don’t learn to manage our impulsive thoughts at all. We just blurt out whatever. We get angry or cry when it isn’t appropriate. We reach for food or alcohol or drugs or sex to calm us, instead of doing something more constructive and effective in the long term.

By now, it’s probably becoming clear: Addiction isn’t a disease. It isn’t a choice. It isn’t genetic. It’s a combination of factors, and the biggest influence is the environment in which we spent our first several years. That environment influenced the development of our brains. It taught us how to behave in order to get our needs met. Often, that meant learning to take care of our own needs, or do without. In order to survive, we suppressed our feelings.

Often, these circumstances where our needs were not met were seemingly mild or minor. Our parents did the best they could, but had their own wounds from their parents. So they were stressed, or angry, or short-tempered. Or busy with work. Or taking care of a sick family member. Or struggling with an addiction of their own. And so, they couldn’t be there the way we needed.

Now, an adult could manage these shortcomings. An adult would understand that people aren’t perfect, and could be forgiving. But to a child, whose world is totally self-absorbed, having our confidence questioned, or being bullied or made fun of, or yelled at, or ignored is completely different. As children, we see everything in the context of ourselves. If Mom is too busy to talk to us, it is our fault. If Dad is angry, it’s our fault or our responsibility to make him happy. And when that happens, all of these experiences add up, and eventually, to deal with our pain, we develop addictive patterns and behaviors.

How those addictive patterns develop, and what the addictions will be, will depend on a lot of factors. Maybe the addiction will be about drugs or alcohol, because that’s what we’re exposed to. Or maybe it will be a pattern of unhealthy relationships. Compulsive video gaming. Overeating. Over-exercising. “Workaholism.” Sexual hook-ups.

The important thing is recognizing that the process of becoming addicted is universal. It isn’t about the drug.What happened to you is important, but more important is what happened inside of you as a result of what happened to you. In other words, how did you process it? Did you have any way to work through it, by talking to someone about it?

Gabor’s experience is that in nearly all cases, those of us who experienced these traumas never had someone to talk to about it. Or if we did, we weren’t believed. It is this – the feeling of aloneness, that we are on our own, and that we must fend for ourselves with this trauma – that creates the addiction process. It doesn’t matter what kind of addiction you have, whether it’s drugs or behaviors. It’s the same brain circuits that are involved. And that’s what makes it a universal addiction process.

Perhaps the single most important take-away of Gabor’s experience with addiction is the hope that can be taken from understanding this perspective. We can stop thinking of addiction as a progressive, incurable disease and instead look at it as the byproduct of wounds we experienced in childhood. And wounds can heal.

Perhaps the wounded area won’t be quite as strong as it might have been if not wounded. So healing from addiction in this case doesn’t mean “able to go back to moderate use” of drugs or alcohol. But it does mean that we can be free of addictive behaviors and cravings. We can rewire our brain, rebuild the damage brain pathways, and teach our brains to produce the brain chemicals we need to be able to feel happy, to be calm, and to live a fulfilled life.

And perhaps best of all, we can break the cycle of addiction that is passed down from parents to children not through genetics, but through our interactions with our children and our own wounds. Breaking the cycle means first, focusing on ourselves: healing the wounds that cause the pain that leads us to addictive behaviors. We heal the wounds by cultivating connections with others. Meaningful, authentic, vulnerable connections, where we feel heard and supported. Where we hear and support others. Connections where we get our needs met, and those we are connecting with also get their own needs met. Connections filled with compassion for ourselves and for others. When we do this, we heal, rebuild, and restore the deficient brain circuits that led to our addictive behaviors.

In many cases, if our families or loved ones are willing, we can also begin to heal the wounds within the family that created the addictive patterns. This requires time, effort, openness, compassion, and patience on both sides. It means breaking down old behaviors and patterns. Learning agenda-less listening and unconditional positive regard.

Unconditional Positive Regard: The ability to separate the person from their behaviors, and to accept them as they are, without trying to change them or judge them. To see them how they see themselves.

Staying respectfully engaged. And giving ourselves – and our loved ones – permission to screw up and going back and trying again.

And for our children, it’s much the same. As Gabor says, the most important condition for healthy brain development is the presence of emotionally available, non-stressed, attuned caregivers. Whatever interferes with the parents’ ability to be non-stressed, emotionally present, and attuned may interfere with the child’s brain development. This means patience. Making time for them. Working on our own wounds, mental health. Actively listening, and seeking out deep connection with them. Accepting their imperfections, and supporting their efforts. Encouraging them and also listening for their needs.

Gabor says “If you get the first three years right, you can probably coast through the next 15 years. If you get it wrong, you’ll probably spend the next 25 years trying to fix it.” So don’t despair if you’ve already lost the chance to get the first three years right. Instead, put your energy into rebuilding the relationships in the same way you rebuild your own brain pathways.

Again… kindness, compassion, patience, agenda-less listening, and unconditional positive regard.